This piece was originally written for the Godspace blog to be a part of their Advent theme Proclaiming Justice, Seeking Peace Through Advent. It was published on 21 December 2022 here. All images by Kate Kennington Steer.

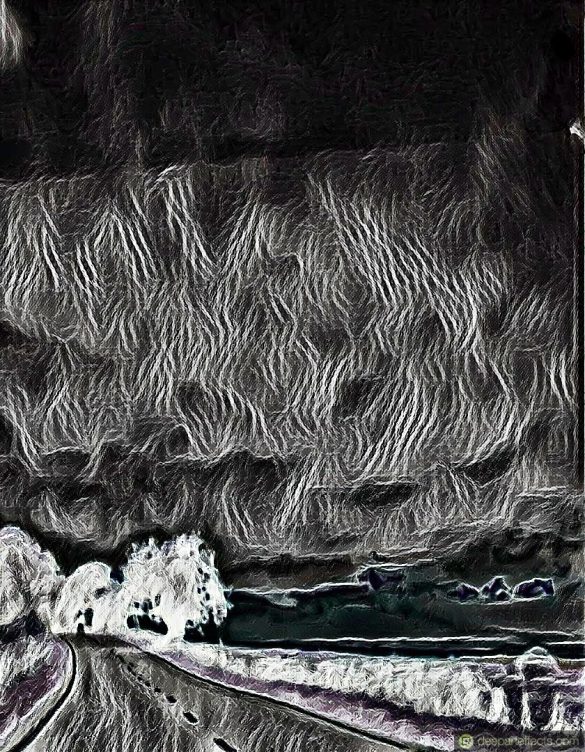

… And if, as autumn deepens and darkens

I feel the pain of falling leaves, and stems that break in storms

and trouble and dissolution and distress,

and then the softness of deep shadows folding, folding

around my soul and spirit, around my lips,

so sweet, like a swoon, or more like the drowse of a low, sad song

singing darker than the nightingale, on, on to the solstice

and the silence of short days, the silence of the year, the shadow,

then I shall know that my life is moving still

with the dark earth, and drenched

with the deep oblivion of earth’s lapse and renewal.

from ‘Shadows’

DH Lawrence

I suspect that many of us have been feeling the ‘pain of falling leaves, and stems that break in storms’ this year. The news seems to be full of people in pain, in so many countries, around our globe. Some countries, like China, still have stringent ‘lockdown’ Covid-19 regimes, with all the increasing social isolation and mental health breakdowns such restrictions bring. Others are being besieged by open warfare, either as an act of national aggression like Russia on Ukraine, or as a result of civil war, like Syria and South Sudan. Some countries are rigidly imposing religious laws that restrict freedoms of speech and movement, like Iran and Afghanistan. Elsewhere, natural disasters are on the increase, a direct result of our human consumption and unjust exploitation, which has induced climates to change and seas to rise. There are droughts and famines and wildfires. There are floods and landslides and earthquakes. There are corrupt politicians, who, in their hunger for power, trample the poor, the sick and the elderly. There are financial crises which put educational, welfare and health systems under strain. There are energy crises… the list seems endless. And behind every one of these global, international, or national level crises, there is are thousands of individuals living in want, in need, in grief and sorrow and strain. There seems so much to fear, so much to mourn. Where is the God of Peace, of Justice, in all this?

A persistent phrase has kept re-emerging in my mind over the last six months:

light is in the horizon yet

I first came across this phrase hearing Eddi Reader’s song ‘light is on the horizon yet’.

This song title was inspired by ‘Do not say that life is waning’, a sixteenth century poem Sir Thomas Moore, the first stanza of which reads:

Do not say that life is waning,

Or that hope’s sweet day is set;

While I’ve thee and love remaining,

Life is in the horizon yet.

By changing ‘life’ to ‘light’, and ‘in’ to ‘on’, Reader expands the nature of the ‘hope’ beyond Moore’s confined use for two lifetimes in love. Reader’s phrase provides us with a wider, less corporeal, more naturalistic, hope; hope which is both of the earth and of the sky. Her image focuses my eyes away from individualistic emotion onto planetary ecology, onto heavenly spirituality.

Predictably, my mind conflated both Moore and Reader by misremembering the line. None the less, over the intervening months I have repeated it to myself many times as a reassuring thread. I find it a reminder to look up and out, but even more than that, a reminder to look for what is often unseen (perhaps particularly for those of us who do not live in a place where a wide vista is possible).

Grief, loss, pain often makes it impossible to remember to look for this unseen light, the elusive light, the dark light. Suffering of any kind blurs, blinds and fogs both my mind and spirit so that I lose my belief in this thin line of light, of life, existing in my own circumstances. At these times I do not even know how to pray this hope into the lives of those who suffer unimaginable conditions elsewhere.

And yet, deep down, there is a knowing in me: there is light in the horizon yet. God is present in the matter and substance of the rocks, earth, hills, plains, prairies, deserts, rivers and seas of that horizon. God is equally present within my details, God is within my every cell. God is a part of how I deal with the pains and problems chronic illness and depression bring. God is a participant in every conversation I have, God is the Source of every prayer I utter.

I find, in these long dark nights around the winter solstice in the northern hemisphere, that looking for the unseen light on the horizon, is an excellent spiritual practice. It helps me better appreciate the riches of the palpable dark, and the rest provided by the very ‘fallowness’ of the season. For within these unseen treasures is the life which does not wane, but renews. That is the secret of these phrases ‘Life is in the horizon yet’/ ‘Light is on the horizon yet’: the power of that small word ‘yet’.

D.H. Lawrence’s poem (above) hints that it is in the places of silence and shadow, those places of ‘low, sad song’, where absence and darkness are at their most potentially fear-inducing, that I shall know that ‘my life is moving still /with the dark earth’. ‘Yet’ may mean waiting through the time of being ‘drenched/ with the deep oblivion of earth’s lapse’, until ‘renewal’ comes, as in the natural turning of the seasons. But ‘yet’ can also mean enduring. I may feel ‘drenched/ with the deep oblivion of earth’s lapse’, mired in the pit of depression with no hope to wait for, but that ‘yet’ points to a deeptime mystery: light and life endures, whether I can perceive it or not.

That is the heart of the ‘hope’ which Blue Christmas enshrines. And those of us who may this year be able to lift our heads, to look into the horizon, and see both life and light, we pray the blessings of that hope over all who cannot pray it for themselves at this time.