(This is the third instalment of ‘well or w/hole?’, and it might (?!) make more sense if you read the other two instalments first. You can find them on the Blog Feed.)

Let’s follow the water…

One line of research around the bright-+/well project led me to think about the ‘well’ in the name BrightWell (see footnote). I am indebted to Neil Moss and his colleagues from the Bourne Conservation Group, who answered some of my questions about the history of wells in Farnham.

BrightWell House sits about a quarter of a mile north of the River Wey, slightly up the chalk Downland. It lies to the southeast of Farnham Castle and Farnham Deer Park which have dominated this part of the North Downs ridge since the seventh century. On the opposite bank of the River Wey, the steep, permeable sandstone hills mean that the water table is particularly deep below the surface. So when wells were dug they had to be dug deep. The first Vicarage of The Bourne (this part of South Farnham, named after the Bourne Stream which is a major tributary of the River Wey) on Vicarage Hill, built in the 1860s, had a well of depth 45m, but apparently this still ran dry and had to be deepened. I can’t quite imagine the engineering effort that must have taken.

Neil Moss told me:

Until the coming of piped water the people of Farnham south of the Wey (in The Bourne etc) needed wells because the water table in the sandstone rocks is very deep. They could have deep wells or, if they could not afford one of those, a “bottle well” which was effectively a chamber in the garden that collected rain. water from the roof. There are several of both types still around: eg the old Bourne Vicarage on Vicarage Hill has a well in the garden and the old Stream Farm House next to the Fox Pub has one. There are also a few bottle wells.

Near the Wey, the water table was only just below the surface so people did not need a deep well, only a sort of scrape. This led to all sorts of outbreaks of disease in the town in the nineteenth century.

Even the Wheelwrights shop described in his book by George Sturt (very close to Brightwell’s) did not have a regular water supply. They had to go next door to get water.

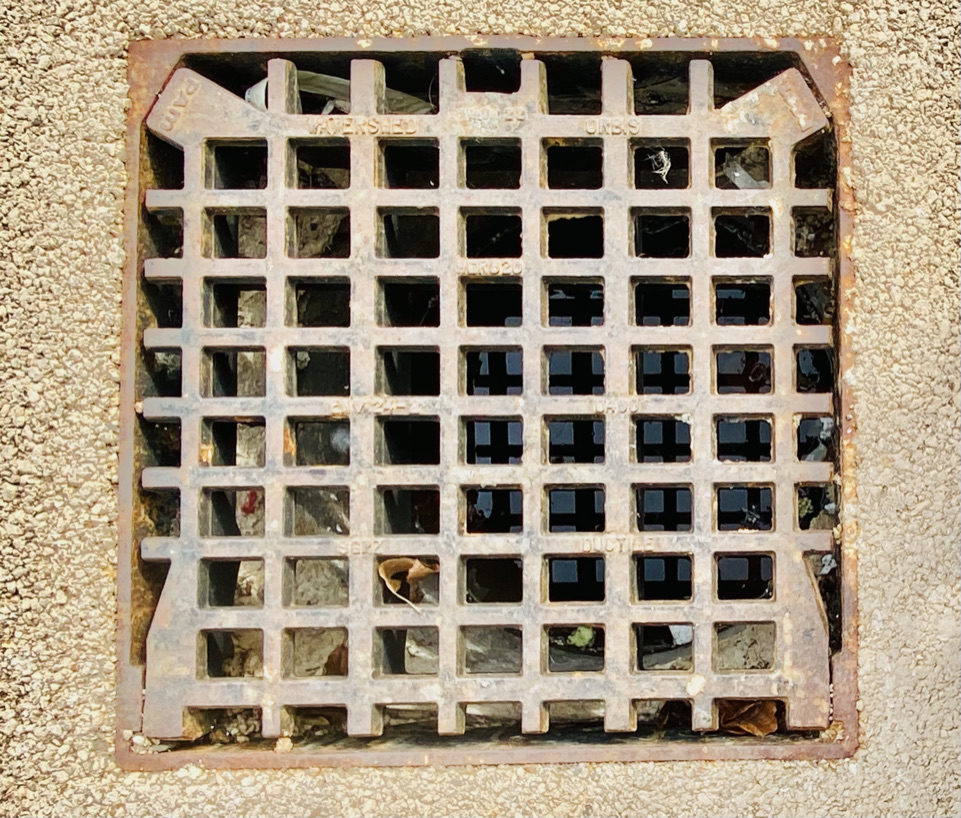

The conduit from the castle kindly provided by one of the Bishops fed into a “reservoir” under the present Nationwide Building Society Office. From there it was pumped up by a hand pump. There was a similar pump Bear Lane [just north of BrightWell House] and quite recently another was discovered in a building in Lion and Lamb Yard. That can now be seen at the Rural Life Museum.

I want to chase down several of Neil’s references, and I also want to talk to someone at South East Water about the history of water supply to houses like BrightWell in the 1790s. Ideally, I want to see old maps and diagrams (which I love, and I always work best with visual illustration). I also have questions for the site managers of Crest Nicholson’s new development BrightWells Yard, to ask what they discovered when they were doing the ground works, if they discovered any springs, ditches or streams, and if they have any historic documentary evidence about the site’s water supply. (I also would love someone to explain to me how you plan water infrastructure for a development of this size). I want to see if I can get more specific information about the historic water-supply along East Street in Farnham, and the land on which BrightWell’s Yard now sits. So many questions!

Yet even without a specific historical anchor, from the beginning of working on this project, I have felt there is something in the name bright-+/well which makes me think of holy wells. This raises all sorts of questions about how humans have made elements of the land ‘sacred’ through time; about how the genius loci, or ‘spirit of a place’, develops a local reputation; and what happens to that ‘spirit’ if one radically changes its’ orientation or usage.

Is there a holy well at Brightwell-cum-Sotwell? And, if this is the village that inspired the choice of a name for a house over a century ago, and if a holy well is present there, does an element of that sacred usage persist in the name when it is transferred to a new place? Or is BrightWell just a name someone liked to call a house, based on where their grandfather might have been born, which has no meaning beyond the familial memory?

According to David Nash Ford’s Royal History of Berkshire, there may be several water-stories and sacred-stories connected with BrightWell-cum-Sotwell:

You cannot see the join between these two villages today but, in Saxon times, they were a little distance apart. Since that time, they have always been separate parishes and Brightwell is actually split in two by Sotwell running through the middle. The name of the greater neighbour was originally Beorht-Wille which may have meant ‘Bertha’s Spring’. Bertha was the Saxon Goddess of sacred springs and the Moon, indicating this was a sacred pagan area. A more boring interpretation is ‘bright spring’. It was sometimes called West Brightwell or Brightwell Episcopi to differentiate it from Brightwell Baldwin in Oxfordshire. Sotwell may mean ‘South Town Spring’. Mackney, the southern portion of the parishes, means ‘Macca’s Island’. So the springs must have created a number of streams which cut this area off from the rest.

The Roman road from Silchester to Dorchester-on-Thames passed through the parish down Mackney Lane. The ford where this road crossed the River Thames is one of the traditional sites of the baptism, by St. Birinus, of King Cynegils of Wessex and a large proportion of his Court, in the presence of King Oswald of Northumbria. It was mostly a political rather than a devotional act, for Cynegils wished to forge an alliance with the Christian King Oswald. The latter would only agree, however, if Cynegils would give up his pagan ways and marry Oswald’s daughter. St. Birinus’ arrival on the scene was merely opportune. King Cynegils gave Dorchester to Birinus so he could build himself a church (or cathedral) within the old Roman walls. These were the beginnings of the See of Wessex. Birinus became its first Bishop and remained so until his death in AD 649. His shrine at Dorchester became a great place of pilgrimage, but controversy later arose when the Bishop moved his seat to Winchester and claimed to have taken the body of Birinus with him.

As ever, all this leaves me with more questions than answers, or even approaches to answers, about the interconnections between holiness and a sacred use of certain sites, which are often focussed on water. But, aside from historical and intellectual curiosity, one question persists in me as a spiritual reality for my own life:

for someone who feels neither well nor holy, what is a holy wellness? Or a ‘well’ holiness?

And when I turn to thinking about the spirituality of wellbeing and the relationships between bodies and buildings, could the placement of a well in a particular place, at a moment in time, provide some suggestive strategies for our modern need to create in our built environment specific places in which wellness is actively sought: body, mind and spirit?

The bright-+/well project is allowing me to have all sorts of conversations with people who are serious about living these nuances.

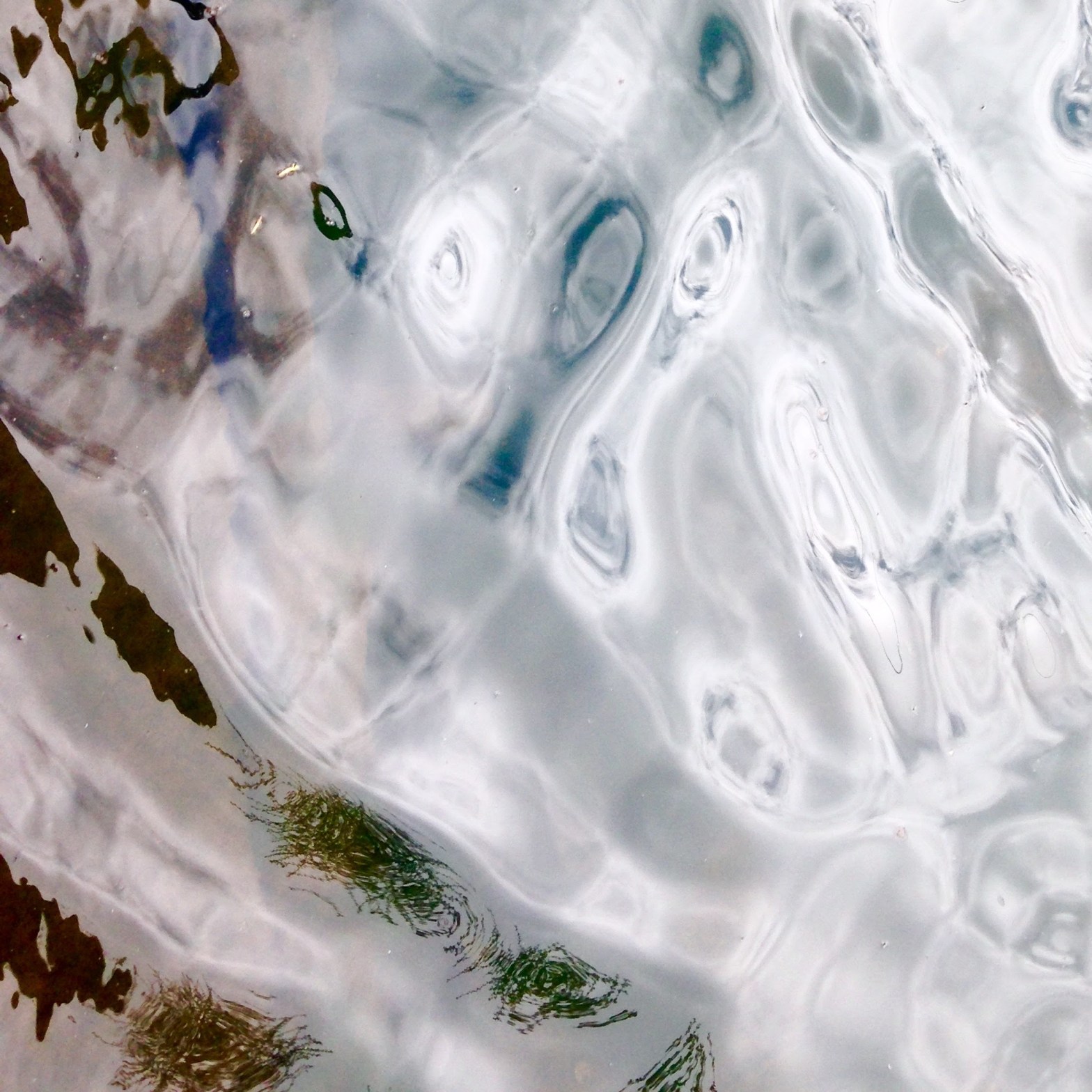

(could this be what’s left of a luminous holy/wholly well?)

footnote:

the bright -+/well project:

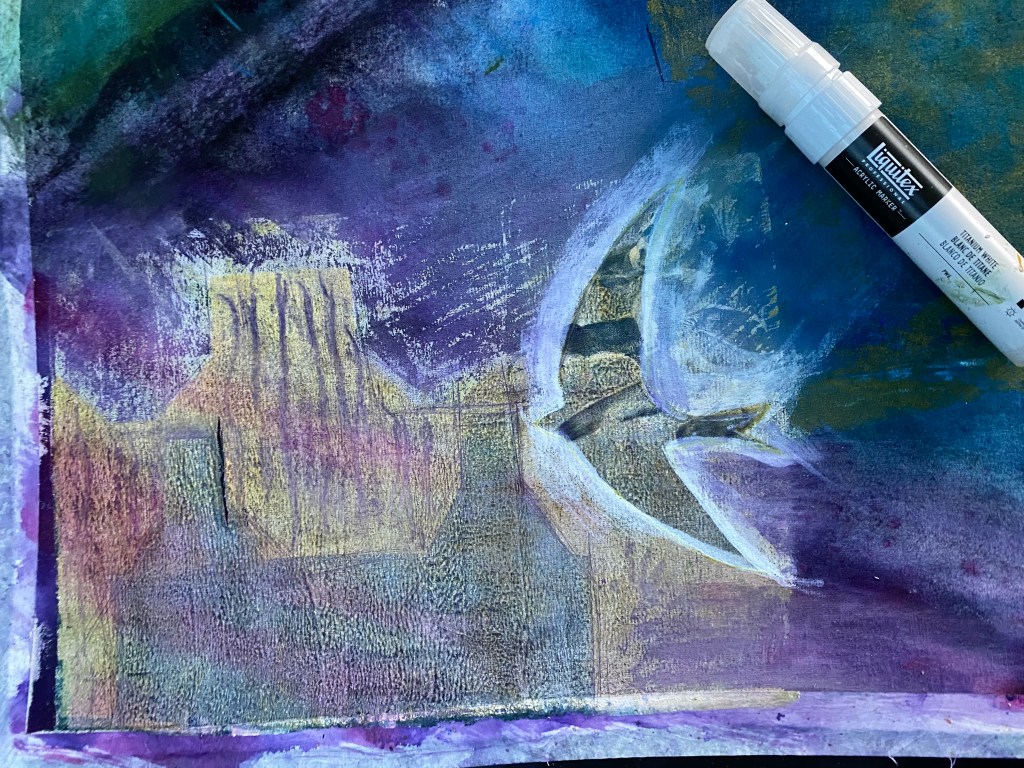

I am experimenting with ways to combine, layer and merge photography, painting, printing and poetry around four main themes:

- how a single space/place changes through time;

- how the people of each era leave their vestigial marks on the landscape;

- how the act of building an urban environment affects the well-being of those whose labour crafts our homes, shops, offices;

- as well as how the finished built environment affects the wellbeing of those who live in, work at, or visit to, that place.

I am exploring these themes with reference to a single place: a new town-centre, mixed commercial and residential development by Crest Nicholson PLC, named BrightWells Yard in Farnham, which has a Grade II listed Georgian house called BrightWell at its heart, in which I used to work in 1998, when it formed a part of the Redgrave Theatre.